- Home

- Caroline Stelllings

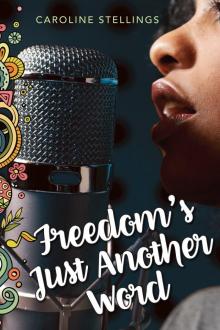

Freedom's Just Another Word Page 12

Freedom's Just Another Word Read online

Page 12

“Git your black ass out of here,” he said. Now everyone in the diner was watching, and every single one of them was pleased with what was happening.

“You do know that it’s against the law to discriminate,” I said. I could taste the salty perspiration on my upper lip.

He laughed. “The law? You want the law?” The woman with the purple cheeks laughed too, then said something to the man beside her.

“I’ll call my cousin. He’s the sheriff. I’m sure he’ll be happy to drive you out to the county limits.” He laughed. “He’s got a rifle in his trunk.”

“Let’s go,” said Marsha. She was pale with fright.

“I’m from Canada,” I said frantically, as if that would make a difference.

“Negro-loving Canada. Home of the free,” said the cook/waiter/owner. He opened the door and stood there with his foot in it. “Go back to Canada. They can keep you. But git your goddamn black ass out of my diner, or I’ll string you up to that tree out back. Do you hear me?”

Marsha prodded me out the door. Through the front window of the diner, I could see all the smiling and leering and laughing faces, and I felt completely humiliated. Degraded. Ashamed, even. Of what, I don’t know, but I was ashamed.

Ten thousand Miss Poultices, twenty thousand George Penns—nothing could ever add up to what it felt like to be thrown out of that restaurant.

Marsha put an arm around me and I saw tears in her big, scared eyes. Then she hugged me, and I wanted to cry. I didn’t—I couldn’t, because it would have meant that horrible man had won. But I wanted to. I wanted to yell out loud or throw a brick through the window or get a skywriter to spell B-i-g-o-t over his stupid diner. But trying to grab hold of my emotions was like trying to catch minnows with my fingers; everything slipped away from me, and all I could do was let Marsha hug me. I think it probably did her more good than me, since by the way she hugged me—with flat hands against my shoulders—I could tell she wasn’t used to hugging. Maybe she’d never been hugged in her life. And because she was so sharp-cornered, a hug from Marsha felt like being squeezed between a pair of two-by-fours.

I was sick and asked Marsha to drive, and we drove and drove and drove and drove. She said nothing; I said nothing. When we came upon another restaurant, Marsha went inside and brought out milkshakes and fries for us, while I waited in the car, covering my face when anyone walked by. This time I was the one who could only manage a few bites; my appetite had disappeared, and I felt as if I would vomit even the smallest mouthful of food.

Because it was after midnight by that time, and we had long since given up hope of locating the parish, I convinced Marsha that we had to sleep in the car. There was no way I was going to try to check into a motel—not without Sidney Poitier, the Negro Motorist Green book, and a bulletproof vest.

After an hour of feeling sorry for myself, and going over everything Thelma had told me about how she and Clarence had dealt with the most abysmal situations, I emerged from the darkest part of my tunnel of misery. Still, I wanted a distraction, so I struck up a conversation with Marsha. I didn’t care what she had to say, I was ready to listen.

“So have you decided on a name?” I asked her. “Is it going to be Bohuslava? God’s glory?”

“Yes, Louisiana, I think that Bohuslava is the name I will take.” She said it with the kind of mystic reverence normally reserved for an eclipse of the sun, but there was ketchup on her face, which detracted from the whole “God’s glory” thing.

“How come you never call me Easy?” I asked her, figuring it was because she didn’t believe in anything that wasn’t difficult.

“I prefer to call you Louisiana,” she said, sounding more like a schoolteacher than a traveling companion.

She opened up the car door to look at the sky. It was brilliant with sparkling stars, and Marsha seemed lost in thought. When the air began to cool down, she closed it again and stretched out along the front seat. I moved to the middle. I couldn’t sleep for the longest time, but felt drowsy, and started up another chat—the kind that you can only have when you’re half asleep.

“Why did you decide to become a nun?” I bravely asked.

Marsha didn’t answer at first, then finally replied, “I had a calling.”

“You mean like Jesus appeared in your room one night?”

“Something like that.”

I didn’t believe her. I knew that she’d chosen to do it so she could be better than everyone else.

“What did your parents say?”

“They don’t know yet.”

“Don’t know yet? But—” I had to think for a minute to do some calculations. “You’ve been a postulant for months now. You’re taking your name in October, so you’ve been a postulant for…”

“Three months.”

“So you haven’t seen your parents since April?” I asked.

“February.”

“February? Don’t you like your parents?”

“It has nothing to do with like or dislike,” she said. “They are traveling in Europe.”

I tried to find out if she ever wrote to them, or if they ever called her, but Marsha snipped off between her teeth any loose threads of our conversation. I got the picture that she had been raised in a cold family and could see why she didn’t know how to hug. When I first met Marsha, I figured that something in her childhood had turned her sour—maybe some kid had called her “toothpick legs” or peeled all the wrappings off her crayons. After a while though, I realized that her problems stemmed from something deep-seated. I didn’t feel sorry for her exactly, but I didn’t detest her quite as much, once I knew she’d been starved of affection.

Marsha finally drifted off to sleep, her faint snoring sounding like a fly buzzing behind a curtain. I guess I fell asleep too, because before I knew it, the sun was beginning to stretch and yawn, the air inside the car was hot, and Friday, the tenth of July, had finally arrived. I awoke with a tight, expectant feeling, and with the coming of morning, life didn’t seem nearly as bad as it had the night before. The anticipation of singing with Janis overrode the idiots at the diner by a Texas mile.

I threw myself into the driver’s seat and managed to find the Interstate fairly quickly. After a week of travel, it dawned on me that I was about to meet my destiny, and it felt like the wheels of the station wagon never hit the highway. I was so excited to think that Threadgill’s and Janis were at the end of the road that nothing else mattered. Even Marsha seemed different to me. Although she didn’t jump for joy, she didn’t complain about my singing the way she usually did; I guess she knew I had to practice. I did Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday songs mostly, but I threw in some Janis too.

It was right after I sang “Piece of My Heart” that Marsha reminded me that she would not be going to Threadgill’s, not even for a minute, and would be going straight to the convent in Austin. She planned on spending the day there before returning to Albuquerque on Saturday. She made it clear that she’d rather take a picnic lunch to the morgue than go with me to the bar.

“But Mother Grace said your assignment was to meet Janis,” I protested. “You aren’t going to lie to her, are you?”

“I feel too ill to go.”

“No, you don’t.”

“Yes, I do.”

“You’re not sick.”

“Am too.”

Big baby, I thought. “Well, I won’t say anything. I’m not a rat. But you’re missing out on the experience of a lifetime. I mean, c’mon, this is Janis Joplin we’re talking about. Pearl!”

“Pearl?”

“That’s what she calls herself, when she wears the feather boas and wild clothes,” I explained. “That’s what she told me to call her!”

“What a vain and self-centered thing to do. She should be happy with the name her parents gave her,” she said, her lips folded in like a buttonhole.

“You

’re changing your name, aren’t you?”

“That’s different. A nun takes a new name to show that she has given up her life to serve God.”

“No, it isn’t different at all. Janis has given up her life in order to serve the public. As a performer.”

“Rubbish,” said Marsha. “That name Pearl—well, it sounds like something a whore would use.”

“You’re wrong,” I said. “I remember Thelma telling me that pearls are the result of sand getting into the shell of an oyster. The irritation is what makes the silky fluid flow.”

“So?”

“She said it’s like trouble in your life. Without it, you don’t amount to much. Without something abrasive, you never find out what you’re made of. I think that’s why Janis chose that name. Because life’s been tough on her, but she realizes that without her problems, she’d never have become such a great singer.”

Marsha didn’t reply for a long time—several miles at least.

“Anyway,” I continued, “I think Pearl is a wonderful name.”

“I think it sounds cheap. Is it her intention to sound common?”

“I don’t know,” I admitted, looking at my watch. “But we’re nearly there, so why don’t you change your mind, come to Threadgill’s, and ask her yourself?” I wrinkled up my forehead and scowled. “What are you afraid of?”

“Nothing. I don’t want to go there, that’s all.”

“I thought nuns were supposed to go places they didn’t want to. Learn about life in the gutter.”

Marsha sneered, then I sneered, but since we were getting close to Austin, I pulled over so that she and I could change places. I wanted to read the map carefully so we didn’t miss our exit, and I didn’t trust Marsha to do it right.

Once we were back on the road, and I was sure we were on track, I decided to bug her again. “Didn’t Mother Grace say the Grey Nuns were brave women who risked their lives to help people sick with typhus and cholera?” I hadn’t listened to everything she’d told us about the history of the order, but I remembered that part.

Marsha didn’t say a word. But she knew I was right.

I don’t know why I argued with her. I didn’t want her to come to Threadgill’s, and I didn’t care about her career as a nun. Maybe I was too nervous to go there alone, and Marsha was better than nothing.

Maybe it was worse than that.

Maybe I was afraid of what I had to face once I got inside.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Marsha pulled into Threadgill’s and waited while I took my suitcase, accordion, and frottoir out of the back of the yellow submarine. It was one of those toe-tapping waits that said she wanted the hell out of there. At least my lecture about the Grey Nuns had put a temporary stop on those knife-edged statements of hers. She still looked like she was smelling something putrid, though, every time Janis was mentioned.

“I’ll be staying at the convent tonight,” she told me. She had rolled the window down an inch, and was talking to me through the crack. “Will you be returning to Albuquerque with me tomorrow?”

“No,” I said. “I’m hoping Mr. Threadgill asks me to stay. Or better yet, maybe Janis—I mean, Pearl—will ask me to come to California with her.”

Marsha rolled up the window.

“Wait!” I hollered.

“What is it?” This time she opened the window only half an inch.

“Well…uh…good-bye. I hope things—you…” Trying to say good-bye to Marsha was impossible, partly because I was talking to my own reflection in the window, and partly because she was so anxious to get away that she kept letting up on the brake and jerking the car ahead.

“Yes. Thank you. Take care.”

She sounded more like a pharmacist than a friend. Okay, maybe we weren’t pals exactly, but take care? She drove off in that same choky cloud of dust as she had on the first day I met her, being sure not to let any part of her gaze fall on Threadgill’s. I waved. She didn’t. And that was that.

Electrified with hope, but feeling like I’d just boarded an ocean liner with no ticket and no passport, I made my way to the front door. The place was brimming with people, too many to count, and when I asked a guy, he told me that the gathering was to celebrate Ken Threadgill’s birthday. He also said that Janis wasn’t there yet.

Tobacco smoke had discolored the whitewashed walls of the converted gas station, and bluegrass music reverberated from every one of them. I squeezed my way in and wondered how, in all the chaos, I was ever going to get Janis’s attention.

A waitress saw my instruments and assumed I was with one of the bands; she had eyebrows that were two hairs wide with azure-blue shadow underneath each one. She pulled me through the crowd to where the musicians had put their stuff, and showed me a safe place to leave my suitcase, not far from the stage. She handed me a beer and didn’t ask for I.D.

When I saw an older guy in a cowboy hat I guessed that he was Threadgill, since he was clearly the center of attention. He wasn’t dressed up, and seemed like a laid-back kind of guy. Not pretentious at all. The band played a country tune, then pushed him to a microphone. He sang “T for Texas,” an old favorite that wasn’t exactly a favorite of mine, but everyone around me loved it. I hoped that when Janis came, she’d sing some blues, then I could do the same.

Maybe she’s forgotten all about the Southern Comfort and all about me.

Maybe she’s not coming.

Maybe she decided to go directly to Los Angeles.

I set my instruments on a chair and found another for myself. A middle-aged man with Brylcreem in his parted-down-the-middle hair plunked himself next to me. He smelled like stale wine with a dash of garlic and a hint of tooth decay, and I wondered why it’s always the ones with the worst breath that are the most anxious to corner you.

“You know, a few years ago, you couldn’t have been here,” he said, like he was telling me something I didn’t know. Like I wasn’t aware that the place was once a segregated venue.

I didn’t reply.

I looked around though, and realized that everyone was white.

Why didn’t I notice that right away? This is Austin, for God’s sake. Why did Janis ask me to come here? Threadgill doesn’t want me to play in his bar. He’s only doing it as a favor for Janis.

Maybe she’ll take me with her to California.

Confusing thoughts swirled around in my head, and my self-confidence was dragging somewhere around my ankles.

“A few years ago, you couldn’t have—” His breath was so strong, you could get high on a few whiffs.

“I was asked to come here.”

“Okay.” He put his arm around me and I stood up.

“You look tired,” he said. “Let’s get out of here and go to my place.” He rose from his chair and tried to shove me against a wall. I was trying to decide whether to kick him in the groin or yell “Fire!” when the waitress who’d given me the beer grabbed him by the back of his collar and turned him over to a bouncer.

“Thanks. A lot,” I said.

“Don’t mention it,” she told me.

Before she got away, I confided in her. “Will there be trouble with me being here?” Then I added, “I’m from Canada, and well, I’m not familiar—”

“We follow the law, honey,” she said. And while it was comforting to hear that I wasn’t going to be thrown out by the scruff of my neck the way Mr. Brylcreem had been, knowing that I was being tolerated because Threadgill had no choice made me feel about as welcome as a skunk at a garden party.

“Threadgill’s a racist?”

“No, not really. He’s just trying to run a business. Doesn’t want any trouble.” She shrugged. “Keep to yourself and there’ll be no problems.”

Keep to myself? Don’t mingle with dem white folks?

The waitress picked up her tray

and vanished into the crowd.

Just as I began to wonder why Janis had asked me there in the first place, every head swiveled around in the direction of the side door. I knew it had to be her without even looking. Sure enough, people starting yelling out her name and whistling.

She strolled confidently to the stage area, not far from where I stood. I took a good look at her; she was as vivacious as ever, but her eyes were redder than before, half-closed and murky.

She was high on heroin.

She grabbed Threadgill, threw a necklace of flowers around his neck, then hollered out in an exaggerated Texas drawl, “I brought you the one thing I knew you’d like, Ken—a good lei.” One thing about Janis, she didn’t hold back.

It turned out she’d just been to Honolulu, because the next thing she said was, “I can’t play rock’n’roll without mah band, and mah band is in Hawaii.”

Good, I thought. Then she can sing some blues songs instead.

After she and Threadgill gave each other far too many hugs and how-have-you-beens, everyone screamed for her to take the stage. She stumbled up the step, then asked for a guitar. She had arrived with an entourage of people—who they were, I had no idea—but one of them appeared to be a manager or agent or something, because he clenched his teeth like a movie director then handed her a six-string.

“I can’t tune it. I can’t tune worth shit,” she complained. “Somebody tune this thing.”

Somebody did, and she sang two Kris Kristofferson songs. Because country music ranked with elevator music in my mind, I was disappointed at first. “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” was okay, and everyone laughed when she joked, “almost as bad as Tuesday morning coming down, or Thursday morning coming down.” Judging by the way she was sucking on her Southern Comfort (not the bottle I’d given her—she’d probably gone through a dozen since then) and by the fresh needle tracks on her arms I glimpsed when she pulled up her sleeve to hold the guitar, I’d say she’d had a lot of experience in coming down.

But none of that—not the alcohol, nor the heroin, nor the fact that she was singing country tunes—detracted from hearing her sing “Me and Bobby McGee” live and from only a few feet away. Her voice penetrated my body and soul like nothing ever had before. Like nothing ever would again.

Freedom's Just Another Word

Freedom's Just Another Word