- Home

- Caroline Stelllings

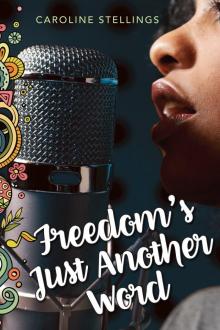

Freedom's Just Another Word Page 10

Freedom's Just Another Word Read online

Page 10

“Can you pull me back in?” He reached for my arm and tugged, but I didn’t know what to do, so he let go.

Mother Grace and Marsha came to tell us it was time for lights out.

“You can stay where you are, Roy,” she added. “But there is a clean bed if you want it.”

He didn’t answer her, and grabbed my arm again instead. I tried to break free, but the Mother Superior gave me a look that meant Let him hold your arm. He needs to hold your arm.

“You’re going to Woodstock to see Janis Joplin. I heard you say that.” His eyes were still out of focus, so it felt weird answering him.

“No, I’m not.”

“I heard you say you’re meeting Janis Joplin. Can I come to Yasgur’s Farm with you?” he asked.

“Uh…I…I’m not going to Woodstock. I’m going to Austin to meet her. She’s going to help my singing career. I hope.”

Roy said nothing for a full minute, but never let go of my arm.

“Janis Joplin, she could do it,” he said. “She could pull me back in. Could I hold her arm?”

“Do what?” Marsha grumbled.

“Hold Janis Joplin’s arm.”

Mine was starting to get pins and needles in it, but I didn’t move.

“And how would that help you?” asked the Mother Superior.

“She’s been down. She’s been down, I can tell by the way she sings.” He dropped his head, then pulled it up again. “Can I come with you to Yasgur’s Farm?”

“Woodstock was last year, Roy.” Mother Grace wiped her eye with a napkin; I could see that she was truly concerned for Roy and didn’t know what to do. Then she turned off the lights, and once Marsha and I came through, she shut the door behind us.

“You’re staying in there, aren’t you?” asked Marsha, intimating that I was suited more for the mission than the convent.

“Yes, I just want to put my accordion back in the car.”

Mother Grace looked up at the sky, then at me, then at Marsha, like she was trying to figure something out. Finally, she told us what was on her mind, and I don’t know which one of us was more shocked, Marsha or me.

“I’ve made a decision on your placement, Marsha,” she said, this time with a stern voice, quite unlike the one she’d been using in the mission.

“You have?” Marsha beamed, but not for long.

“If Easy will agree to it, I’d like you to go to Austin and meet Janis Joplin. That’s what I want you to do.”

“I don’t know if I can take anyone with me,” I protested.

“I assume the bar is open to the public,” declared the Mother Superior. “I realize that I am asking a lot of you, but—”

“Please, Reverend Mother,” begged Marsha. “Anything but that. Anything. I don’t like the woman and I don’t want to meet her.”

“My mind’s made up,” she said. “Easy, if you will take Marsha with you, we could help with your expenses. We don’t have much in the way of money, but I’m sure Sister Beatrice will let you take the station wagon, and you could stay with our sisters in Austin.”

“But I have to go to Amarillo first. I’m delivering something to a friend there. For my father.”

“Fine. You can stay at St. Michael’s Parish. It’s on the road between Amarillo and Austin. I have good friends there.”

This woman has friends everywhere, I thought.

“No, please, Reverend Mother. I’d rather stay here and learn from you,” cried Marsha.

“Since you find so many things wrong with Janis Joplin, I think she’s the one to teach you about people. And drug addiction.” She set her jaw. “My job is to train you to do mission work, and I think that meeting her will do more than I ever could. It’s very easy to see the dark side of drugs—any fool can do that. But until you find out what attracts young people to them in the first place, you will never be able to help anyone.”

“But—”

“I’ve made my decision. And there’s one other thing—I want you to take Roy along.”

Marsha said nothing, but had an expression on her face that if audible would have been something like: you can put red-hot nails in my eyeballs but I’ll never do it.

“Roy’s tried to kill himself twice. Next time, he might be successful. Maybe if he met Janis Joplin, talked to her, and held on to her arm…” She bit her bottom lip. “The boy is desperate. Please take him.”

I didn’t know how to respond, but Marsha did.

“Maybe if you threatened him. Told him he couldn’t stay at the mission unless he quit doing drugs. That would make him stop.”

“No,” said Mother Grace. “Absolutely not. This is the one place he can come without judgment. No demands. The world is enough of a threat for Roy. This is God’s house, Marsha. God’s house accepts everyone, no questions asked.” She turned and went back to the convent.

“What about Sister Beatrice?” hollered Marsha. “I’m supposed to stay with her.”

The Reverend Mother kept walking. “She’ll be here when you get back,” she said.

Marsha waited for the door to close behind the nun, then gave it to me straight. “I might have to go to Austin with you, but I will not set one foot in that bar. Not one foot. And there’s no way I’m taking Roy. I refuse to travel with a drug addict. It goes against my principles, and I will not do it.”

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

It wasn’t long after seven that I awoke to the squeals of children and the crack of a bat hitting a baseball. From the window beside my bed, I saw Mother Grace and a bunch of children in a nearby field; it was obviously a team practice, since she was banging balls into the air for them to catch. A battered old school bus was parked nearby, so I figured they’d soon be on their way to a game.

I got dressed and headed out the back door, into the grassy area behind the convent. The rising sun stained the eastern sky like spilled salsa, and I could already feel the heat of the day building. In Saskatoon, it would have taken until noon. I got to thinking about the garage and wondered how Larry and Clarence and Gillie were doing. Maybe it was because I was so far from home, or maybe it was all that talk of prostitutes the night before, but I started thinking about that god-awful Wendy Wood again too. I detested thinking about her, and while I was normally quite successful when it came to erasing her from my mind, I’d spent the entire night hating her and wondering how—how could Clarence have been attracted to such a woman? Didn’t he love Thelma enough to resist? He did love Thelma—I knew that—so why did he do it?

My thoughts were interrupted when two nuns whisked past me with a small ladder and headed to the bus. One held the ladder while the other threw up the hood. She studied the engine for a long while. The confused look on her face reminded me of Thelma when she decided to learn a bit about auto parts so she could help us in the garage. It was a hopeless cause and we had laughed about it many times thereafter.

God, I miss you, Thelma.

You help those women with their bus, Easy, she told me, so I did.

“Anything I can do?” I asked the nun with the ladder.

“I hope so. Do you know about engines?”

“Do you?” asked the one under the hood. “Mother Grace is supposed to take the team to Santa Rosa, and the bus won’t start. Do you know anything about these things?” She came down the ladder, and the other nun handed her a rag to wipe the grease off her hands.

“I’m a mechanic,” I said triumphantly. “Let me take a look.”

I quickly realized that the bus was badly in need of new spark plugs and a general overhaul. I checked the oil too, and it was dirty. It hadn’t been changed in a year or more.

“When’s the last time you had the bus serviced?” I asked. Both nuns shrugged, which told me my suspicions were correct.

“Will it go, Easy?” yelled Mother Grace, surrounded by a team of young ball players. “I couldn’t

get it started this morning. Can you fix it?”

I found a loose ignition wire, and was able to connect it without tools, and I managed to clean out the intake ports. One of the nuns started up the engine and all the kids cheered. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much to cheer about.

“Listen,” I said, “this bus needs a lot of work. You might get to Santa Rosa, but there’s a good chance you won’t get back. Those plugs are in bad shape.” I felt guilty for not taking time to fix it for them, but I would have needed a crescent wrench and pliers and more time, not to mention spark plugs and maybe an ignition coil. I couldn’t risk delaying my trip to Austin any longer, and Mother Grace knew it. It made me feel selfish, but damn it all, this was the chance of a lifetime.

“You can’t keep Janis waiting,” she said with a wink. “We’re expecting some used parts to come in as donations. And we’ll get to a garage once our budget allows for it.”

That really made me feel guilty. (Even guiltier than I did for sponging all those meals off the pope.)

The kids piled into the bus, then hung out the windows and cheered again. The two nuns did too. I really wished they hadn’t, since those young faces beaming at me made me feel like a self-serving creep.

The Reverend Mother drove. I hoped they all prayed because they were going to need divine help. I couldn’t see the terminals on the coil without taking everything apart, but from experience I knew that once the wires start getting loose like that, it’s time to replace everything. I would have done it for them, but she was right—I had to get to Austin by Friday, and I wasn’t about to let anything, or anybody, get in my way.

Part of me—the part generated by Wendy Wood—wanted to take off right there and then and hitchhike my way to Amarillo. I wished that the Mother Superior had not asked me to take Marsha; traveling with her was the equivalent of attending a hundred funerals. And I wasn’t sure how well Roy would travel, either.

But I liked Mother Grace, and didn’t want to disappoint her, even if Marsha had no intention of meeting Janis Joplin. Frankly, I was glad, because I didn’t want anything to stand in the way of my success. A postulant hanging around would have put a damper on the whole thing. So if it meant traveling with Marsha to Austin, I’d have to put up with it; at least I could save a few more bucks. Up to now, the trip had cost me next to nothing, so I had lots of cash ready, should Janis ask me to come with her to Los Angeles. Or New York. Or the moon. I crossed my fingers, loaded my stuff into the car, and called for Marsha. She appeared from behind a tall cactus, and was as pale as a cadaver.

“Hurry, let’s go,” she said, looking over her shoulder, like we’d just robbed a bank and the yellow submarine was our getaway car.

“Where’s Roy?”

“I can’t find him, and we don’t have time to search for him, so let’s just go, okay?”

“You mean you don’t want to find him, Marsha,” I said. “That’s not very postulant-ish of you, is it?”

“He’s gone. He’s nowhere to be found. Let’s get a move on.”

“She dresses like a prostitute, she talks like a prostitute, and lives her life like a prostitute,” mumbled Marsha from the passenger seat, still seething from having to make the trip to Austin.

“You weren’t exactly born in a manger, you know,” I said. Not that we know of, anyway.

Marsha didn’t reply, so I gave it to her. “I don’t think it was right for us to leave without Roy. Mother Grace asked you to take him.”

“Why should I?” she snapped. “I’ve spent my entire life trying to stand for something other than drugs and alcohol and iniquity.”

“I dunno—I thought this was supposed to be your chosen line of work. Helping people. Helping drug addicts.” I shook my head.

“I have chosen to be a nun, and must go where I am told. Things will change. I won’t have to work with addicts forever.”

“I still think you should have tried to help Roy. He’s desperate.”

I said no more, and kept on driving, intending to stay at the wheel for the full four-hour drive to Amarillo. That way I could make time when there was nothing to see, and slow down when I wanted to take in the sights along Route 66. We’d already made our way through the twists and turns of Tijeras Canyon, past innumerable white concrete buildings advertising Mexican dishes, the classic turista types standing in front, smiling for a camera.

“I can’t eat anything Mexican,” protested Marsha, when I suggested stopping for lunch at the Casa Grande Diner in Tucumcari. “I’ll have heartburn for the rest of the day.” While it was good to know she had a heart in there someplace, I was nevertheless determined to sample the tacos and other spicy foods that I’d heard so much about. So while I went inside and had lunch, Marsha waited in the car, sulking like she did at the used-car dealership.

The Casa Grande was not only a tourist stop, but also a gathering place for the locals, and when I sat down at the counter, I noticed immediately that the conversation going on beside me was the same one I’d heard at the last diner: Route 66 and what the building of the Interstate highway was going to do to the Mother Road. Despite the grinding beat of Sly and the Family Stone singing Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Again)—a song that beckons you to stand up and dance—everyone in the place had sober faces, and kept pointing at the road and shaking their heads.

The midday sun was starting to bake the concrete outside; Marsha had finally succumbed to the heat inside the station wagon, and had planted herself against a big elm tree with a girth the size of four men. The bark was covered with the dried skeletons of locusts that had shed their skins.

“That girl’s going to get those bug bodies in her hair,” said a man near me, looking out at the postulant.

I laughed under my breath.

“It’ll do her good,” I said.

“She’s your friend?” he asked.

“Not really,” I said. “Just a traveling companion.”

Unfortunately, one of the waitresses switched the radio to a country and western station, which meant nothing but songs about lost love, bad luck, and railroads. It also meant turning my thoughts to Larry, and I began to wonder how everyone was doing back home. I picked out another postcard—this one had a map of the Mother Road on it, with a star that said You are here, in Tucumcari. On it I wrote:

Hello everyone,

I’m on the road to Amarillo and expect to be there in a couple hours. Don’t worry, the medalsare safe. I’ll write again after I see Janis!

Once I come down to earth.

Love, Easy

While I wrote my message, the guy to my left watched. He did try to look away, but the seats were so close together, he’d have to cover his eyes or go to the washroom again if he wanted to avoid reading what I’d written. I decided to give the guy a break.

“It’s just a note for Clarence and Larry back home in Saskatoon,” I told him.

“Your family?” he asked, after a couple of swallows of black coffee.

“Clarence is my father. And Larry’s from Porcupine Plain,” I added as an afterthought.

“Where the hell’s that?” asked a man seated to my right.

“Saskatchewan,” I said.

“I’ve been to Saskatoon a few times, making sales,” he said, “but never heard of Porcupine Plain.” He clunked down his mug. “Good people in Saskatchewan.”

“Never been there,” said the first guy. “Hear it’s cold. Lots of wheat.”

“Saskatoon’s all right,” I said, “but there aren’t too many opportunities for a singer like myself.”

“Country singer?” asked one of them.

“Blues singer,” I replied. “At least, I will be soon. Up to now, I’ve been working for my father as a mechanic.”

“Your father has a garage up there?”

“Yeah. We do regular stuff, but he specia

lizes in classic cars.”

“I’ve got a Model-T back home in Chattanooga,” said the salesman. “I’m fixing it up. Gonna be a beauty.”

“Bring it up the next time you come to Saskatoon, take it to Merritt garage and ask for Clarence,” I said. “He’s got parts for Model-T’s that you can’t find anywhere else. Side windows, caps, stuff like that.”

“I will, I will.”

“Too bad about Route 66,” I said, and they both nodded in agreement.

Then the guy on my left chuckled. “Canadians all say Root 66.”

“Americans all say Rowt 66,” I replied.

I realized at that point that although the two men had been quite amiable, the waitress hadn’t said a word the entire time. Just stood there, chewing her gum. It went through my head that maybe she didn’t approve of a black girl sitting at the counter.

That’s just Denver talking. Put it out of your mind.

“Interstate just ain’t the same. No friendly faces, no history, no nothing,” said one of the men.

I stood up, and fished for money in my pocket. “I’m taking Route 66 to Amarillo. I’ve got to drop off some war medals for my father.” I said good-bye, then paid the waitress. She mumbled, “Good day,” but didn’t really mean it. Maybe she was racist, maybe she was simply a quiet person.

I guess I’ll never know.

“Was your father in the war?” asked the salesman as I was leaving.

“Yeah. On a ship. But the medals were awarded to a friend of his who died. I’m taking them to his mother.” I was going to mention the fact that he was one of the first black men to ever be awarded the honor but declined, thanks to my new-found paranoia about racism. I wasn’t as self-conscious back in Saskatoon, even after what Miss Poultice and George Penn put me through. Now I was.

I asked the waitress if there was a mailbox nearby, and she gave me some vague instructions about a box next to the Reptile Ranch down the road. Since I wasn’t too fond of poisonous rattlesnakes, I jammed the card into my purse and figured on mailing it later.

I took a cold drink out to Marsha. She said grace, took a tiny disinterested sip, then got back into the car; I returned to driving, minding my own business and trying to enjoy the trip. When we crossed from Quay County, New Mexico into Deaf Smith County, Texas, (and lost an hour, moving instantly from Mountain to Central Time) the sun disappeared, and there was a taut stillness in the air; it was about to storm. Curtains in motels and motor courts were poised in the middle of a sway, half in and half out of the window, and the trees were bent, listening for the sound of the rain to begin.

Freedom's Just Another Word

Freedom's Just Another Word